|

|

|

|

|

Old

lava flows near the Fang Glacier.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A

Coal in the Icebox

|

|

by

Noel Wanner

December

10, 2001

Paul

and I just got back from six days up on Mt. Erebus, the volcano

that looms over everything down here. We drove a snowmobile

to the rim of the crater through a fantastic landscape of

snow, ice fumaroles, and lava towers. At 12,500 feet, with

the wind howling, we looked down from the ice-encrusted rim

into the bubbling, steaming lake of red lava below—a

furious island of heat in the midst of the ice.

|

|

|

|

|

Emperor

Penguins sunbathe

.

|

|

|

|

|

|

On

this continent, every living creature has its own pocket of

heat it needs to survive. Every bit of warmth is precious

for life. Some organisms have evolved to tolerate low temperatures

that would kill other organisms—tiny

Notothenoid

fish with "antifreeze" proteins in their blood

—while

others like Emperor penguins and Wedell seals have thick insulating

layers of fat and feathers or fur to help them retain their

body heat. Penguins allow the temperature of their feet to

fall close to freezing, thereby lessening the temperature

gradient between their feet and the ice beneath them. This

smaller gradient slows the rate of heat loss, allowing the

penguins to expend less energy keeping warm.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Paul

stays warm on the rim of

Erebus.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We

humans are not so well adapted to cold, so we have to compensate

with the clothes we've invented. The problem is that our internal

heat production varies widely with our level of activity.

As a result, we spend our time on the ice in a constant flurry

of clothing adjustment, trying to keep our internal temperatures

relatively constant. I keep thinking that we must look as

comical to the penguins as they look to us-- frantic naked

apes festooned with colorful cloth, shivering and jumping

about, while the Emperors calmly stand and preen their feathers.

|

|

|

|

|

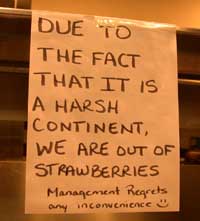

No

berries for dinner tonight

.

|

|

|

|

|

|

On

Erebus, Paul and I were staying with a group of geophysicists

at a semi-permanent camp about two miles below the summit.

There were two huts with kerosene stoves providing heat where

we could eat and work when the weather turned bad, which it

did for about two days— minus 30 C and 40 knot winds,

resulting in a wind chill of about -60 C, plus a blizzard

of blowing snow and sulfurous vapour from the volcano. However,

each night we all slept in our tents, dug into the snow pack

outside—by far the coldest nights I've ever experienced.

To stay warm, we cocooned ourselves in thick sleeping bags.

In the morning, the collected moisture from my breath would

be condensed on the inside of the tent in a thick layer of

frost, which would then rain down on me like a miniature indoor

snowstorm. This, as you might imagine, does not improve your

mood in the morning. But we get up and put on our layers of

clothing. Outside, the wind howls. We go out to do our work,

alongside the scientists—another day of nursing our warmth,

struggling to preserve the coal in the icebox.

|